This post is an expansion of my own notes from working on our new About page. You can check that out for a quicker overview and cooler pictures.

Let’s say you have one bottle of Dasani. Just one. But on the table in front of you sit two dozen potted tomato plants, just beginning to bear fruit. What do you do?

Do you divide the water fairly between all twenty-four, even though each would get less than an ounce? Maybe give the water to just a few, so they actually grow? Drink the water yourself and learn to like tiny, green tomatoes?

Today we're looking at a problem parallel to this tomato teaser. How much of their limited attention can any teacher give their learners? For a long time, we’ve operated as if only two choices exist. Option One—limit learners to increase per capita attention—or Option Two—scale over everything. But I think there’s an Option Three.

For Option One, we flip to the front of the history book. Back in Aristotle’s time, the mid-300s BC, teachers work with very few learners. Aristotle teaches only a few aristocratic pupils at a time. Later, Jesus educates at a teacher-disciple ratio of 1:12 (excluding his TED Talk-like addresses). Da Vinci manages an even lower ratio—more like 1:7.

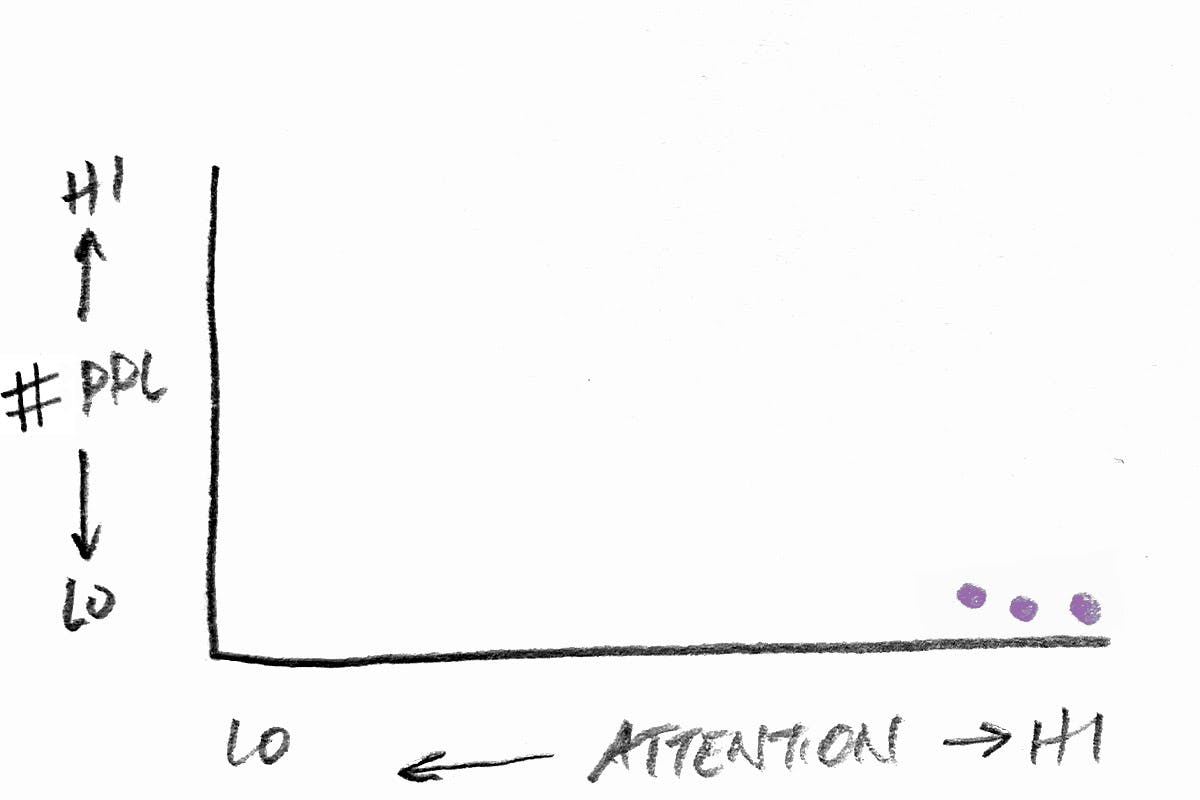

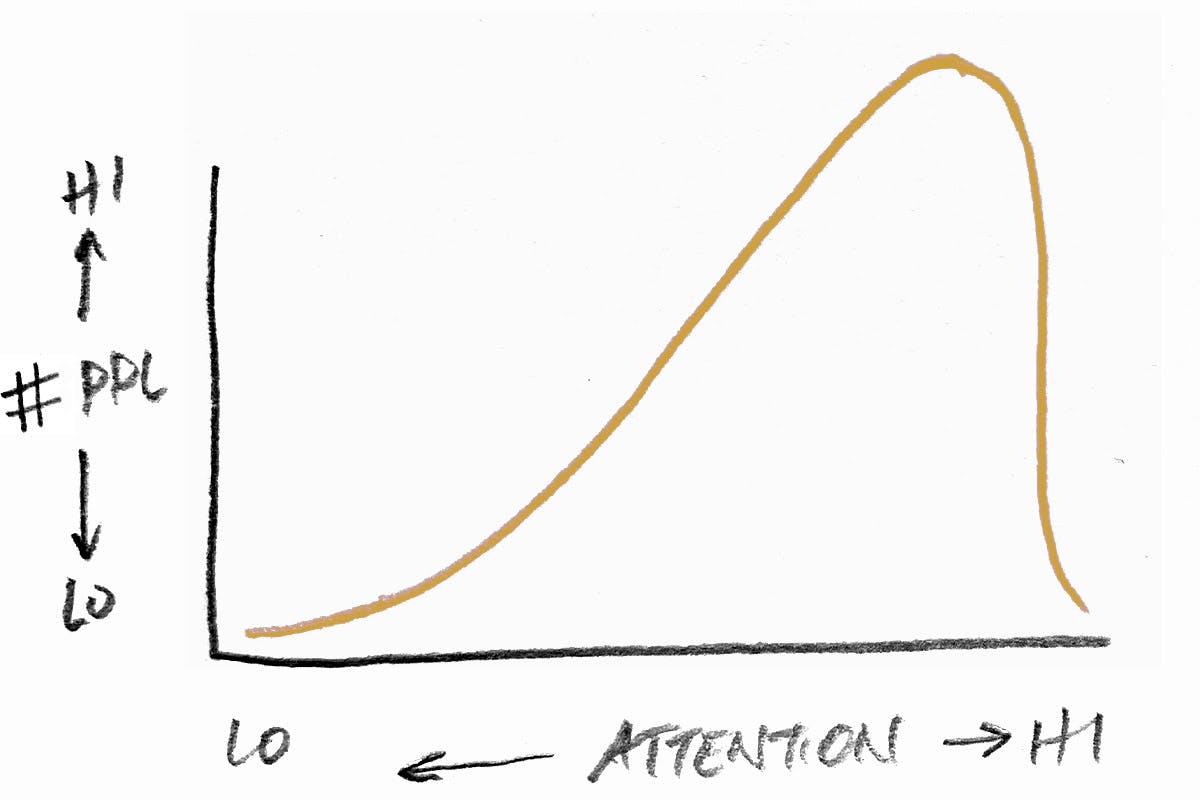

Let's start graphing. I know, I know, I'm excited too! But settle down, please.

We draw one axis for how many learners each educator teaches at once—"# PPL." Now we draw another for how much attention each teacher could afford per learner—"ATTENTION." Our apprenticeship examples in purple fall on the far right. Low number of people, high amount of attention.

Okay, we flip forward in history. Now we're in the 1700s and 1800s. This era marks the rise of what’s sometimes misleadingly called industrialized education. The teacher-learner ratio changes; we find Option Two.

In Europe and North America, smart folks like Horace Mann wonder how to make educated citizens out of their diverse, far-flung populations. They begin developing a concept we'll later call the "common school"—the seeds of our modern public education system. As education goes national, they discover a new appetite for scale. I’d like to think those early meetings must have sounded like start-up pitches—“But how will it scale?”

Education leaps from a few learners at a time to dozens at once.

We flip further to the back of the history book. Starting in the 1920s, radio helps audiences experience arts, education and entertainment as it happens. Everyone watches the 1969 Apollo 11 mission on TV. Fred Rogers uses his show to reach 1.8 million homes at its peak in 1986. Geography and history game “Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?” sells more than 4 million copies by 1995. The learner masses grow to almost inconceivable scale.

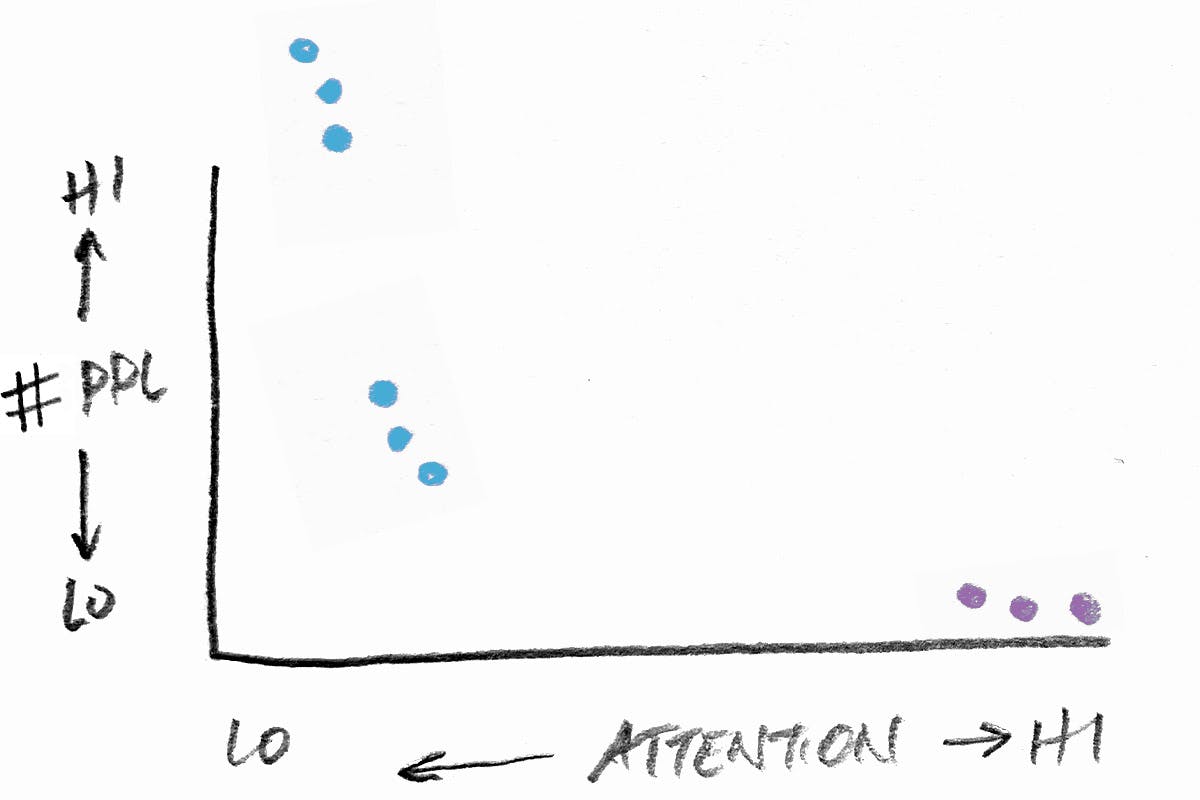

Let's revisit our attention-to-people graph and add Option Two. A few blue dots for public school in the middle, a few at the far left for mass media.

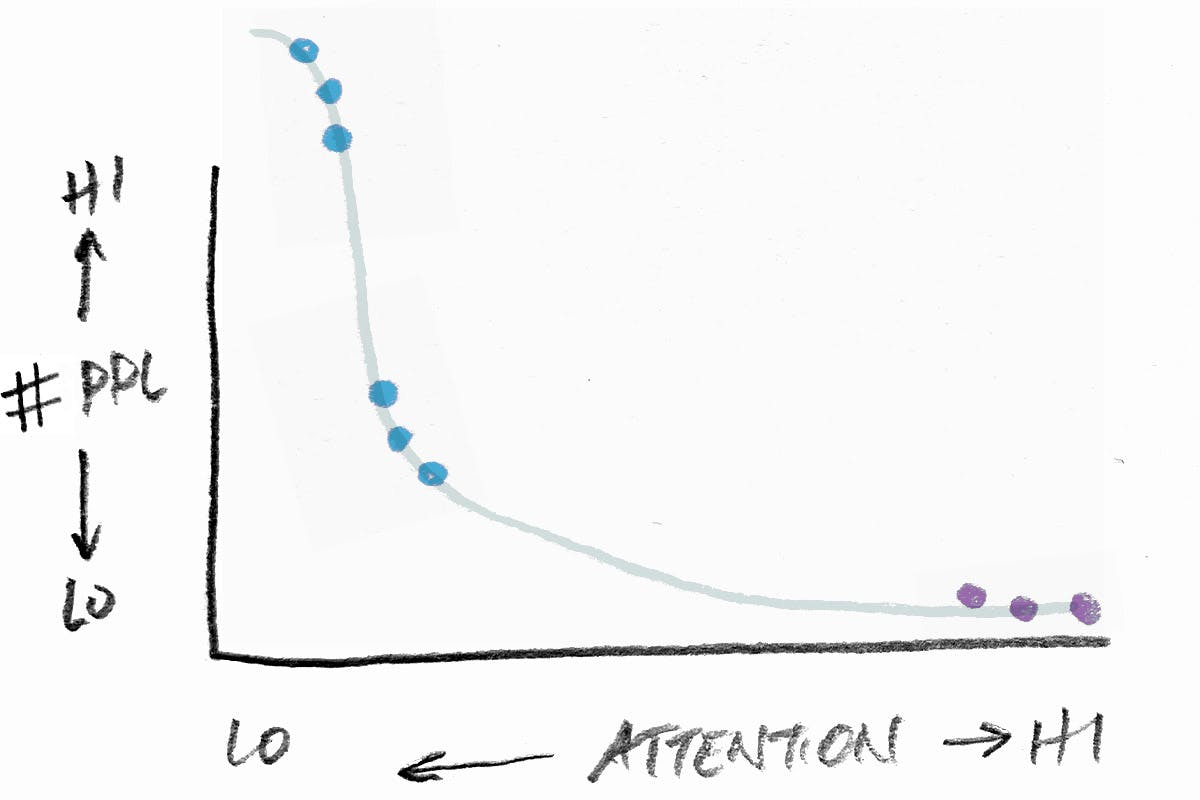

When we draw a curve to connect all of our points so far, we get this:

It looks like Option One and Two combined to create a system that biases toward giant settings. Most learners represented on our graph would be in the head, with very few filling out the long tail. We can tell that teachers figured out how to give a few drops of attention to a lot of learners at once. Learners, on the other hand, don't receive much personal attention unless they're long-tail outliers. This system bias results in extreme efficiency but risks efficacy in the process.

Earlier, I dangled the possibility of Option Three. What would a third way look like?

At Pathwright, we've spent the last decade working to balance the curve with thoughtful, creative educators and organizations. We gave customer Krista King the features to personally tailor thousands of her individual learners’ paths just for them. Fellows programs like the C.S. Lewis Institute used Pathwright to scale their high-attention mentorship. They scaled to many new cities while helping supervisors give the timely attention their fellows need to explore through independent study.

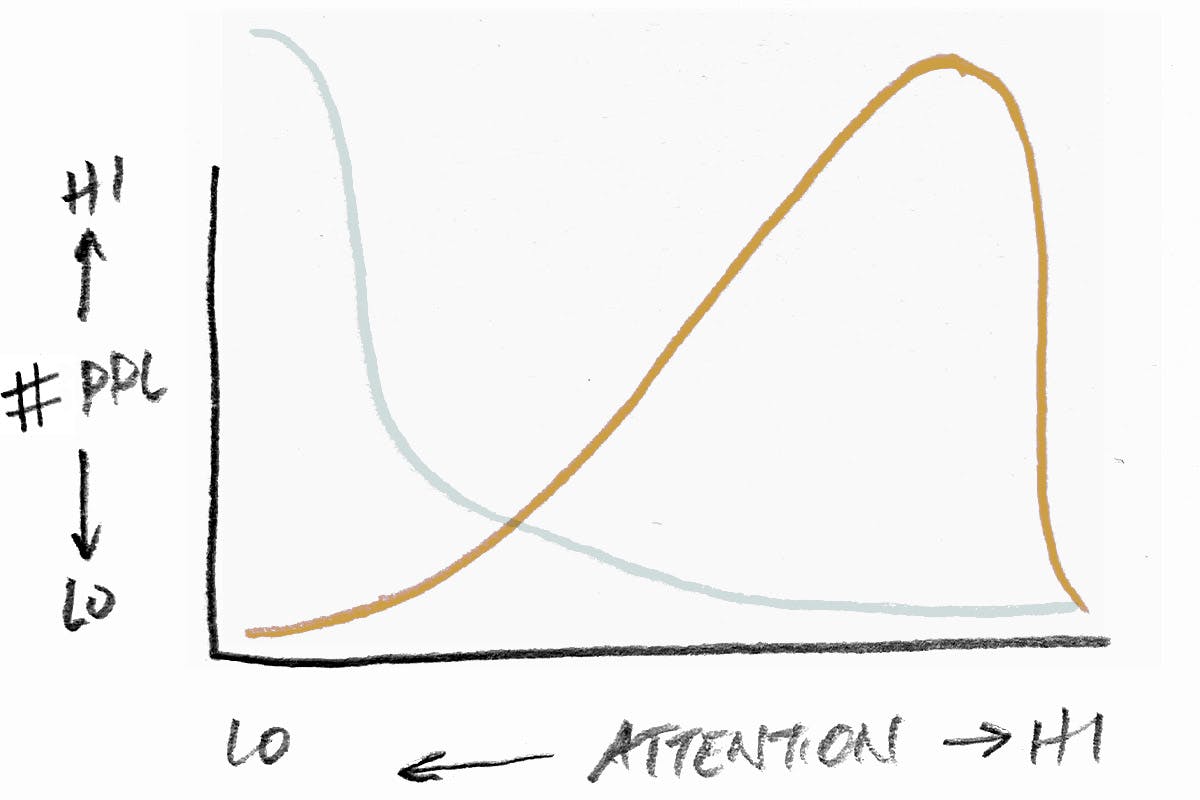

Option Three uses a modern learning platform like Pathwright to share engaging learning with a personal touch. If we draw the curve our customers created, we get something very different:

This curve accounts for a few turnkey courses on the left tail. But it scales both attention and learner headcount nicely, for the first time. To compare, here’s the curve Option One-Two created, overlaid with our Option Three curve.

What does this mean?

It seems to me that education has wound through the phases of a start-up over the last few millennia. It incubated in tribes and apprenticeship settings. It launched a compelling MVP in the 1700s and 1800s as education went to market at scale. But now it’s upgrade time.

I think education deserves to get out of beta, don’t you?

Both schools and organizations work better with clear paths and close connections. At Pathwright, we’ve seen giant institutions use well-designed paths with effective teachers to bring their scale down to each learner. So I'm certainly not suggesting closing schools. We’ve also seen two-person operations scale out to serve thousands. So apprenticeship isn't dead either.

We think you should be able to scale your attention with your learners—our amazing educators provide the proof. We’re not here to change the world (you’re doing that already). We’re working to give you the creative tools you need to keep doing it without having to choose between attention and scale ever again.

Give every plant the water it needs to grow.

Again, this post draws from my own notes as I worked on our new About page. All of these ideas wouldn't fit on that page. If you have a sec, check out our About page for a more fast-moving, visual overview of what we're here to do.

Using Pathwright is dead simple and doesn’t cost a thing until you’re ready to launch a path.

Get startedTopics in this article